Kaon

| Composition |

K+ : su |

|---|---|

| Statistics | Bosonic |

| Interactions | Strong |

| Symbol | K+ , K0 , K− |

| Types | 3 |

| Mass | K± : 493.667±0.013 MeV/c2 K0 : 497.648±0.022 MeV/c2 |

| Electric charge | K± : ±e K0 : 0 |

| Spin | 0 |

In particle physics, a kaon ( /ˈkeɪ.ɒn/, also called a K-meson and denoted K[nb 1]) is any one of a group of four mesons distinguished by the fact that they carry a quantum number called strangeness. In the quark model they are understood to contain a strange quark (or antiquark), paired with an up or down antiquark (or quark).

Kaons have proved to be a copious source of information on the nature of fundamental interactions since their discovery in 1947. They were essential in establishing the foundations of the Standard Model of particle physics, such as the quark model of hadrons and the theory of quark mixing (the latter was acknowledged by a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2008). Kaons played a distinguished role in our understanding of fundamental conservation laws: the discovery of CP violation (a phenomenon generating the observed matter-antimatter asymmetry of the universe), which was acknowledged by a Nobel prize in 1980, was made in the kaon system.

Contents |

Basic properties

The four kaons are :

- The negatively charged K−

(containing a strange quark and an up antiquark) has mass 493.667±0.013 MeV and mean lifetime 1.2384±0.0024×10−8 s. - Its antiparticle, the positively charged K+

(containing an up quark and a strange antiquark) must (by CPT invariance) have mass and lifetime equal to that of K−

. The mass difference is 0.032±0.090 MeV, consistent with zero. The difference in lifetime is 0.11±0.09×10−8 s. - The K0

(containing a down quark and a strange antiquark) has mass 497.648±0.022 MeV. It has mean squared charge radius of −0.076±0.01 fm2

. - Its antiparticle K0

(containing a strange quark and a down antiquark) has the same mass.

It is clear from the quark model assignments that the kaons form two doublets of isospin; that is, they belong to the fundamental representation of SU(2) called the 2. One doublet of strangeness +1 contains the K+

and the K0

. The antiparticles form the other doublet (of strangeness −1).

| Particle name | Particle symbol |

Antiparticle symbol |

Quark content |

Rest mass (MeV/c2) | IG | JPC | S | C | B' | Mean lifetime (s) | Commonly decays to (>5% of decays) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaon[1] | K+ |

K− |

us | 493.677±0.016 | 1⁄2 | 0− | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.2380±0.0021×10−8 | μ+ + ν μ or |

| Kaon[2] | K0 |

K0 |

ds | 497.614±0.024 | 1⁄2 | 0− | 1 | 0 | 0 | [a] | [a] |

| K-Short[3] | K0 S |

Self |  [b] [b] |

497.614±0.024[c] | 1⁄2 | 0− | (*) | 0 | 0 | 8.953±0.005×10−11 | π+ + π− or |

| K-Long[4] | K0 L |

Self |  [b] [b] |

497.614±0.024[c] | 1⁄2 | 0− | (*) | 0 | 0 | 5.116±0.020×10−8 | π± + e∓ + ν e or π± + μ∓ + ν μ or |

[a] ^ Strong eigenstate. No definite lifetime (see kaon notes below)

[b] ^ Weak eigenstate. Makeup is missing small CP–violating term (see notes on neutral kaons below).

[c] ^ The mass of the K0

L and K0

S are given as that of the K0

. However, it is known that a difference between the masses of the K0

L and K0

S on the order of 3.5×10−12 MeV/c2 exists.[4]

Although the K0

and its antiparticle K0

are usually produced via the strong force, they decay weakly. Thus, once created the two are better thought of as composites of two weak eigenstates which have vastly different lifetimes:

- The long-lived neutral kaon is called the K

L ("K-long"), decays primarily into three pions, and has a mean lifetime of 5.18×10−8 s. - The short-lived neutral kaon is called the K

S ("K-short"), decays primarily into two pions, and has a mean lifetime 8.958×10−11 s.

(See discussion of neutral kaon mixing below.)

An experimental observation made in 1964 that K-longs rarely decay into two pions was the discovery of CP violation (see below).

Main decay modes for K+

:

-

Results Mode branching ratio μ+

ν

μleptonic 63.43±0.17% π+

π0hadronic 21.13±0.14% π+

π+

π−hadronic 5.576±0.031% π+

Error no symbol defined Error no symbol definedhadronic 1.73±0.04% Error no symbol defined Error no symbol defined Error no symbol defined semileptonic 4.87±0.06%

Decay modes for the Error no symbol defined are charge conjugates of the ones above.

Strangeness

The discovery of hadrons with the internal quantum number "strangeness" marks the beginning of a most exciting epoch in particle physics that even now, fifty years later, has not yet found its conclusion ... by and large experiments have driven the development, and that major discoveries came unexpectedly or even against expectations expressed by theorists. — I.I. Bigi and A.I. Sanda, CP violation, (ISBN 0-521-44349-0)

In 1947, G. D. Rochester and Clifford Charles Butler of the University of Manchester published two cloud chamber photographs of cosmic ray-induced events, one showing what appeared to be a neutral particle decaying into two charged pions, and one which appeared to be a charged particle decaying into a charged pion and something neutral. The estimated mass of the new particles was very rough, about half a proton's mass. More examples of these "V-particles" were slow in coming.

The first breakthrough was obtained at Caltech, where a cloud chamber was taken up Mount Wilson, for greater cosmic ray exposure. In 1950, 30 charged and 4 neutral V-particles were reported. Inspired by this, numerous mountaintop observations were made over the next several years, and by 1953, the following terminology was adopted: "L-meson" meant muon or pion. "K-meson" meant a particle intermediate in mass between the pion and nucleon. "Hyperon" meant any particle heavier than a nucleon.

The decays were extremely slow; typical lifetimes are of the order of 10−10 seconds. However, production in pion-proton reactions proceeds much faster, with a time scale of 10−23 s. The problem of this mismatch was solved by Abraham Pais who postulated the new quantum number called "strangeness" which is conserved in strong interactions but violated by the weak interactions. Strange particles appear copiously due to "associated production" of a strange and an antistrange particle together. It was soon shown that this could not be a multiplicative quantum number, because that would allow reactions which were never seen in the new synchrotrons which were commissioned in Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1953 and in the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in 1955.

Parity violation

Two different decays were found for charged strange mesons:

-

Error no symbol defined → Error no symbol defined + Error no symbol defined Error no symbol defined → Error no symbol defined + Error no symbol defined + Error no symbol defined

The intrinsic parity of a meson is P=−1, and parity is a multiplicative quantum number. Therefore, the two final states have different parity (P=+1 and P=−1, respectively). It was thought that the initial states should also have different parities, and hence be two distinct particles. However, with increasingly precise measurements, no difference was found between the masses and lifetimes of each, respectively, indicating that they are the same particle. This was known as the τ–θ puzzle. It was resolved only by the discovery of parity violation in weak interactions. Since the mesons decay through weak interactions, parity is not conserved, and the two decays are actually decays of the same particle, now called the Error no symbol defined.

CP violation in neutral meson oscillations

Initially it was thought that although parity was violated, CP (charge parity) symmetry was conserved. In order to understand the discovery of CP violation, it is necessary to understand the mixing of neutral kaons; this phenomenon does not require CP violation, but it is the context in which CP violation was first observed.

Neutral kaon mixing

Since neutral kaons carry strangeness, they cannot be their own antiparticles. There must be then two different neutral kaons, differing by two units of strangeness. The question was then how to establish the presence of these two mesons. The solution used a phenomenon called neutral particle oscillations, by which these two kinds of mesons can turn from one into another through the weak interactions, which cause them to decay into pions (see the adjacent figure).

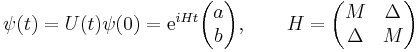

These oscillations were first investigated by Murray Gell-Mann and Abraham Pais together. They considered the CP-invariant time evolution of states with opposite strangeness. In matrix notation one can write

where ψ is a quantum state of the system specified by the amplitudes of being in each of the two basis states (which are a and b at time t = 0). The diagonal elements (M) of the Hamiltonian are due to strong interaction physics which conserves strangeness. The two diagonal elements must be equal, since the particle and antiparticle have equal masses in the absence of the weak interactions. The off-diagonal elements, which mix opposite strangeness particles, are due to weak interactions; CP symmetry requires them to be real.

The consequence of the matrix H being real is that the probabilities of the two states will forever oscillate back and forth. However, if any part of the matrix were imaginary, as is forbidden by CP symmetry, then part of the combination will diminish over time. The diminishing part can be either one component (a) or the other (b), or a mixture of the two.

Mixing

The eigenstates are obtained by diagonalizing this matrix. This gives new eigenvectors, which we can call K1 which is the sum of the two states of opposite strangeness, and K2, which is the difference. The two are eigenstates of CP with opposite eigenvalues; K1 has CP = +1, and K2 has CP = -1 Since the two-pion final state also has CP = +1, only the K1 can decay this way. The K2 must decay into three pions. Since the mass of K2 is just a little larger than the sum of the masses of three pions, this decay proceeds very slowly, about 600 times slower than the decay of K1 into two pions. These two different modes of decay were observed by Leon Lederman and his coworkers in 1956, establishing the existence of the two weak eigenstates (states with definite lifetimes under decays via the weak force) of the neutral kaons.

These two weak eigenstates are called the Error no symbol defined (K-long) and Error no symbol defined (K-short). CP symmetry, which was assumed at the time, implies that Error no symbol defined = K1 and Error no symbol defined = K2.

Oscillation

An initially pure beam of Error no symbol defined will turn into its antiparticle while propagating, which will turn back into the original particle, and so on. This is called particle oscillation. On observing the weak decay into leptons, it was found that a Error no symbol defined always decayed into an electron, whereas the antiparticle Error no symbol defined decayed into the positron. The earlier analysis yielded a relation between the rate of electron and positron production from sources of pure Error no symbol defined and its antiparticle Error no symbol defined. Analysis of the time dependence of this semileptonic decay showed the phenomenon of oscillation, and allowed the extraction of the mass splitting between the Error no symbol defined and Error no symbol defined. Since this is due to weak interactions it is very small, 10−15 times the mass of each state.

Regeneration

A beam of neutral kaons decays in flight so that the short-lived Error no symbol defined disappears, leaving a beam of pure long-lived Error no symbol defined. If this beam is shot into matter, then the Error no symbol defined and its antiparticle Error no symbol defined interact differently with the nuclei. The Error no symbol defined undergoes quasi-elastic scattering with nucleons, whereas its antiparticle can create hyperons. Due to the different interactions of the two components, quantum coherence between the two particles is lost. The emerging beam then contains different linear superpositions of the Error no symbol defined and Error no symbol defined. Such a superposition is a mixture of Error no symbol defined and Error no symbol defined; the Error no symbol defined is regenerated by passing a neutral kaon beam through matter. Regeneration was observed by Oreste Piccioni and his collaborators at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Soon thereafter, Robert Adair and his coworkers reported excess Error no symbol defined regeneration, thus opening a new chapter in this history.

CP violation

While trying to verify Adair's results, in 1964 James Cronin and Val Fitch of BNL found decays of Error no symbol defined into two pions (CP = +1). As explained in an earlier section, this required the assumed initial and final states to have different values of CP, and hence immediately suggested CP violation. Alternative explanations such as non-linear quantum mechanics and a new unobserved particle were soon ruled out, leaving CP violation as the only possibility. Cronin and Fitch received the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery in 1980.

It turns out that although the Error no symbol defined and Error no symbol defined are weak eigenstates (because they have definite lifetimes for decay by way of the weak force), they are not quite CP eigenstates. Instead, for small ε (and up to normalization),

- Error no symbol defined = K2 + εK1

and similarly for Error no symbol defined. Thus occasionally the Error no symbol defined decays as a K1 with CP = +1, and likewise the Error no symbol defined can decay with CP = −1. This is known as indirect CP violation, CP violation due to mixing of Error no symbol defined and its antiparticle. There is also a direct CP violation effect, in which the CP violation occurs during the decay itself. Both are present, because both mixing and decay arise from the same interaction with the W boson and thus have CP violation predicted by the CKM matrix.

See also

- Hadrons, mesons, hyperons and flavour

- Strange quark and the quark model

- Parity (physics), charge conjugation, time reversal symmetry, CPT invariance and CP violation

- Neutrino oscillation

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ The positively charged kaon used to be called τ+ and θ+, as it was supposed to be two different particles until the 1960s. See the parity violation section above.

- References

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (2008): Particle listings – Error no symbol defined

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (2008): Particle listings – Error no symbol defined

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (2008): Particle listings – Error no symbol defined

- ^ a b C. Amsler et al. (2008): Particle listings – Error no symbol defined

Bibliography

- C.Amsler et al.; Doser, M; Antonelli, M; Asner, D; Babu, K; Baer, H; Band, H; Barnett, R et al. (2008). "Review of Particle Physics". Physics Letters B (Particle Data Group) 667 (1): 1–1340. Bibcode 2008PhLB..667....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.018.

- S. Eidelman et al (2004). "Review of Particle Physics 2004 – Strange Mesons". Particle Data Group. http://pdg.lbl.gov/2004/listings/mxxxcomb.html#mesonsstrange.

- S. Eidelman et al. (Particle Data Group) (2004). "Review of Particle Physics*1". Physics Letters B 592 (1): 1. arXiv:astro-ph/0406663. Bibcode 2004PhLB..592....1P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2004.06.001.

- The quark model, by J.J.J. Kokkedee

- M.S. Sozzi (2008). Discrete symmetries and CP violation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929666-8.

- I.I. Bigi, A.I. Sanda (2000). CP violation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44349-0.

- D.J. Griffiths (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particle. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||